Communication from Bert Hofman

Director, East Asian Institute

Professor in Practice, Lee Kuan Yew School

Dear all,

In the last week of July, the politburo of the Communist Party of China is set to meet to discuss economic policies for the second half, before the party leadership takes off to coastal Beidahe to discuss political matters.

The politburo has a lot to talk about. Second quarter GDP growth was barely positive at 0.4 percent compared to last year’s, and achieving the government’s 5.5 percent target seems now increasingly unlikely. Premier Li Keqiang said as much in a meeting with world leaders organized by the World Economic Forum. To reach the 5.5 percent target China’s economy would have to grow by more than 8 percent in the second half, which would require a major stimulus effort that seems increasingly unlikely, and is probably not desirable.

Among all the downward pressures on China’s economy, the property sector stands out. The sector is in disarray after several large property developers last year and earlier this year defaulted on their bonds. The developers had run into problems because of COVID-19 and because government policies to control debt (the “three red-lines” policy) had squeezed their liquidity, and some have halted payments on their loans or bonds obligations. Some developers have abandoned half-built projects, leaving buyers that had put up down payments on properties stranded.

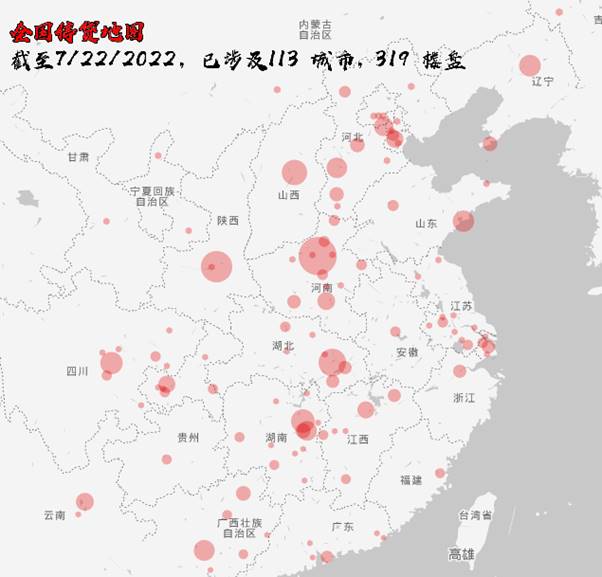

In response, some buyers decided to halt payments on the mortgages they had taken out to pay for the unfinished apartments that may not be completed. According to the “WeNeedHome” crowdsourcing project, some 319 projects in 113 cities are being affected as of July 23. These projects are spread all over China (Figure 1), but concentrated in the central provinces, especially Henan. Furthermore, suppliers to the halted projects are also reported to have halted payments.

The shock to buyer’s confidence has been large. Sales of new apartments had been down by some 35%, in the first five months of 2022 compared to 2021, though June data were slightly better at 20% down year-on-year. In the year until June, housing prices declined in more than 2/3 of the 70 large and medium-sized Chinese cities that the National Bureau of Statistics monitors. The record in other cities, notably tertiary cities, and cities that have been losing population is probably worse.

The sales slowdown is further squeezing developers. According to Chi Lo, an analyst at BNP Parisbas, a bank, the ratio of presales to total new home sales rose steadily from about 58% in 2005 to almost 90% in 2021. Meanwhile, presales accounted for more than half of developers’ financing, as bank financing had dried up to only 11 percent of total financing in the wake of the “three red line” policy aimed at lowering developers’ indebtedness. More than half of the listed Chinese property developers that have so far made first-half earnings estimates expect to have made a loss in the period, according to Yicai, a news website.

Figure 1: Reported halted property projects |

Source: GitHub WeNEed Home Project. https://github.com/WeNeedHome/SummaryOfLoanSuspension/blob/main/data/generated/visualization-light-wwm.png Note that these are crowdsourced data, the accuracy of which cannot be verified. |

As a consequence, developers have slowed new construction. New housing projects starts dropped 45% year on year in June. This in turn is a major draw on the economy: construction is 7 percent of GDP, and real estate another 6.8 percent of GDP. Indirectly, according to investment bank analysis, property could make up even 25-30 percent of GDP (though yours truly is somewhat skeptical of this high estimate). Irrespective, a slowdown in property would obviously cause major problems for the Chinese economy.

Moreover, a slowdown in property spells trouble for local governments. Property developers have also slowed buying land for future development, and land sales, which make up some 1/3 of local government revenues, were down by 65 percent from last June. In addition, a quarter of local tax revenues consist of taxes on property sales. A slowdown in property therefore has major impact on local government financing and spending, and as a result the anticipated government stimulus has hardly taken off. Professor Christine Wong of the East Asian Institute, in a Commentary reckons that local government spending in the year until May was 18 percent below target.

So is this the end of real estate development in China? Or worse, is the growing movement to stop mortgage payments the beginning of the bursting of “The Bubble that Never Pops” as Tom Orlik’s 2020 book puts it?

The risks are not trivial. Most observers would agree that a correction in real estate development was overdue, but a disorderly correction could drag the economy into a recession. And the mortgage strike, a first in China to my knowledge, could hurt the banks.

Total mortgages outstanding by the end of Quarter 2 amounted to RMB41 trillion, or some 40 percent of GDP and a bit less than a quarter of the RMB 172 trillion of bank loans outstanding. Total household debt, at some 60 percent of GDP, or 114 percent of household disposable income is still moderate compared to many OECD countries, but it has seen a steep increase since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

Given the lack of hard data and the fluid situation, it is no surprise that estimates on how much of mortgages could be affected by mortgage strikes vary widely. Morgan Stanley Research puts the mortgages at risk at 2 percent of total at end-Q2. Deutsche Bank reckons the total so far to be at 1.8trn-2trn yuan ($270bn-300bn), or 4.5-5% of the total. Capital Economics, a consulting company, using data of the pipeline of developers’ projects, estimates that up to RMB4trn in mortgage debt (or some 10% of the total) could be at risk.

Even at the higher end of these estimates, the banking system as a whole could absorb the losses. The banks have been profitable in recent years, and have a total provision for bad loans of almost RMB 6 trillion, and NPLs of less than half of that. In addition, tier 1 capital is, at RMB 25 trillion, some RMB 7 trillion more than is needed under Basle III, according to Chi Lo of BNP Parisbas. So on aggregate, the banking system is fine.

If the crisis worsens, though, aggregates hardly matter. Many banks will be fine, but some will still face problems, as has already become apparent in Henan province, where some banks were unable to pay out depositors, which gave rise to riots and heavy-handed intervention by the local authorities. Especially the local banks, which are often enticed to finance the pet projects of local governments, could be at risk. And given the uncertainty, depositors may start pulling money out of banks, even solid ones.

Yours truly is old enough to recall the global financial crisis started as a small issue in the collateralized sub-prime mortgage market in the United States. That market was only 1.5 percent of the total mortgage market in the United States, and even the total sub-prime market was only some 15 percent of all mortgages. Yet, as we now know, that small problem blew up to a financial crisis on both sides of the Atlantic, which caused a global recession.

Yes, China is very different in many respects, but it is no surprise that the authorities are keen to contain the problems. “Preventing the risk of a ‘hard landing’ in the property sector should be high up among our priorities and given serious attention,” said Zhu Guangyao, who was vice minister of finance between 2010 and 2018 and now adviser to the State Council (China’s Cabinet) during an online seminar on July 18, according to a Bloomberg report. Local governments need to handle the boycotts well and “be strictly on guard to prevent it from spreading and triggering a banking crisis,” said Zhu.

What are the authorities doing?

A host of initiatives and proposals are currently addressing the property downturn, and more specifically, the mortgage strike.

For failed developers, the government prefers a time-tested solution: mergers and acquisitions. The People's Bank of China, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission together issued a statement to that extent:

"If a real estate company cannot continue to operate, other real estate companies will acquire the company or purchase the company's projects. At present, a few real estate companies have experienced risk events, and the risk mitigation work of these large companies in the process of exit will be done well. It is very important, and project mergers and acquisitions are one of the important means."

The authorities also encouraged banks to provide the loans needed for such mergers and to revamp lending for property. Such encouragement is usually followed, and de facto it means that the “three red line” policy is suspended.

Apparently, the authorities are considering allowing households to suspend mortgage payments on halted projects. This is remarkable, given the fact that Chinese mortgages are “full resource” i.e. unlike mortgages in the US, you cannot walk away from it and leave the property to the bank. Instead, households are liable for the mortgage debt irrespective of the value of the property, even if it is an unfinished shell.

Meanwhile, local banks are encouraged to rid themselves of their non-performing loans, perhaps in anticipation of more to come. In January to May, small and medium-sized banks disposed of RMB 394.3 billion yuan of non-performing loans, up by 107.2 billion yuan from a year earlier, China Banking and Insurance News reported (via Reuters). These are likely to end up in the many asset management companies that provinces have set up over time. If history is any guide, those banks that will face financial problems will be bailed out by local governments, either through capital injections, or through over-pricing of bad assets as they are transferred to the asset management companies.

Central government, though providing guidance and regulations, wants to stay away from providing financial solutions. This is wise from the perspective of moral hazard: if the center were to provide financing to alleviate the problem, this may make it larger before it gets smaller.

At the same time, the real estate troubles are an additional burden for an already stretched local government, and by not helping local governments, the government’s planned stimulus may be at risk, as noted above. For now, though, requests from some provinces for additional bonds allocations were reportedly denied, though the central government has allowed local governments to use up to RMB320 billion of the special purpose bonds already allocated to recapitalize small banks

There is some discussion of scrapping the pre-sale model for housing development altogether, given the risks involved. In my view, though, this would not be feasible at this time, as it would require major adjustments in the financing model, which could further aggravate the property downturn. Nor would it be desirable from the point of view of leverage of the property developers.

Risks, Moral Hazard, and Development

It is understandable that the authorities want to prevent the unwinding of the real estate sector and controlling the financial risks involved. The drop in consumer confidence in real estate could further depress property sales, which would exacerbate financial troubles of developers and lead to more failures. In turn, mortgage strike could easily expand, which could lead to financial sector problems larger than those experienced today. Even worse, the troubles in property development could lead to a more widespread decline in property prices, and given that some 60-70 percent of household wealth is embedded in property, this could become a major drag on already fragile consumption, and a potential source of social unrest.

At the same time, providing bail-outs for everybody—property developers, prospective buyers and banks—risks perpetuating the misallocation of capital that has been plaguing China for some years now. Indeed, property (and infrastructure) investment have taken a growing share of total investments in China, which has been a key cause of the decline in productivity the country has experienced in the past decade or so. Though property has its return (housing services as measured in GDP), empty apartments meant for speculation or as a vehicle for long term savings do not.

While there certainly is still demand for property in China, it is often not the type that attracts financing from households that want to park their savings. Social housing, in particular rental housing would, at a price, still have demand, but most of construction is at the higher end of the market. Furthermore, demographics suggest that the heydays of China’s property construction boom are over—and that may be the most powerful underlying problem in China’s property market.

So what to do?

First, the government could revamp demand for property. The most obvious demand would come from new residents, and the current property troubles are yet another reason to abolish hukou restrictions on rural citizens. Some cities, including large ones such as Wuhan have already dropped urban hukou as a requirement for buying property. More are likely to follow.

In addition, the government could take the current crisis as an opportunity to accelerate social housing development. In part, they can devote the unfinished housing stock that will land on their balance sheets for such purpose, but for the future, they can play a more active role in social housing, and use appropriate financing sources such as pension funds for this purpose. Pension funds do need returns, but they have a long horizon, and a steady long term return on social housing would fit such a profile.

Second, the government could consider isolating households from the whims of a volatile property development sector. One way to do so is to set up an insurance mechanism against bankruptcy of property developers (and incomplete houses). Such insurance exists in other countries, and at a modest price it insures home buyers against the risk.

China does have a system of “project guarantee” in construction, but this seems more like a performance bond system. The rules require construction companies to seek guarantees for the project for a limited amount, including for faulty engineering and payment of back wages to migrant workers (a persistent problem in China). The deposited guarantee funds are returned to the builder once the project is completed, which is a key difference from an insurance, which would build up balances over time, and spread the risk across many projects. Whereas before the construction companies needed to deposit an amount in escrow, in recent years local governments have been encouraged to switch to bank or insurance company guarantees. Though performance guarantees are important, they fall short of an outright insurance against bankruptcy of a developer.

The crux for a true insurance to be viable is their due diligence on property developers—and only housing that is to be developed by accredited developers should be insurable. Such insurance may need some start-up capital form government in current circumstances, but over time a modest premium would suffice. In the Netherlands, the insurance cost 0.45 percent of the property value.

Alternatively, the government could consider regularizing the option of a mortgage strike, of sorts. This may sound counter-intuitive, but the logic is that the banks that provide the mortgage would be far more careful in their due diligence on the property developer that will build the house for which an individual is seeking a mortgage. And banks are in principle much better equipped than individuals to assess the financial health of developers.

The incentives for the banks to do due diligence would be even stronger, if China were to consider changing the legal model for mortgages from the full recourse model today to a non-resource model, in which the property is the only collateral the bank can take. Such a step would need to be thought through, as it changes the incentives for homeowners. An intermediate step could be that mortgages are to be non-recourse during development, but full recourse after delivery. This would prevent homeowners to walk away from property for frivolous reasons.

One downside of making banks responsible for risk is that banks at the local level are often not independent entities, and could be swayed by local governments to be lenient on shaky developers. More so, if they can easily rid their non-performing loans through local asset management companies, their incentives to do proper due diligence is weak. So an independent insurance organization, at least at the province level, is likely to do a better job, and is also better able to pool the risks across localities.

Third, government would need to speed up the development of alternative investment products for long term savings. Many households see real estate as a means for long term savings, and particularly for pension savings. Given the modest pensions that the public system provides (even for urban workers, the most luxurious system) such long term investments vehicles are in high demand. Developing alternatives and implementing regulations for private pension providers is therefore a priority, as is the further development of the private mutual fund industry.

Finally, the government would need to revamp the fiscal system to make local governments less reliant on property development. Local governments have a strong interest in real estate—even if for speculation—because of the land revenues and property sales taxes as described before. Alternative revenue sources (including a property tax such as the proposals discussed in one of my previous letters) and a bigger share of shared taxes is a start. In addition, central government would need to find better vehicles to implement macro-economic stimulus policies independent from the fiscal situation of local governments. Capital grants are such a vehicle, which will work better than project bonds quota.

I will keep monitoring the travails of property in China and probably write about it more, so I welcome any reaction or any of your writing on the topic. Meanwhile, wishing you happy reading!

Best regards,

Bert